I took this morning’s New Testament reading from the lectionary. It’s an interesting passage for us to consider, because it’s a passage I have heard, many times in the past, weaponised against liberal Christians. We who have abandoned so-called ‘sound doctrine’ and followed after exactly what the passage warns against (at least that would be the charge) - teachings that satisfy our desires, our will, teachings that take us away from the “truth” towards mere myth. I’m obviously a big fan of myth, and was interested to see it used here in 2 Timothy in the pejorative sense, meaning fairy tale or fable. I looked up the Greek word, which is pronounced “mythous”, and I learned that it appears five times in the New Testament, and the word is always used in this pejorative sense, in the sense that we have (or the author has) “the truth”, whereas those ignorant people out there have been deceived by cleverly devised myths.

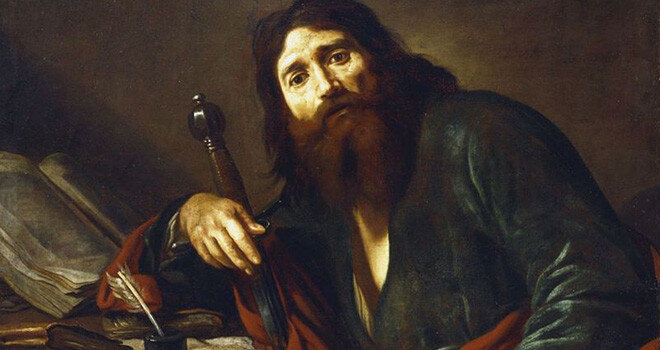

Okay, so let's just put this passage into context. In the New Testament, we have the four Gospels, then the Book of Acts, then a whole bunch of letters, and then the book of Revelation at the end. The majority of the letters are attributed to St Paul, and the key word there is “attributed”, as scholars’ debate which letters were actually written by Paul, which ones may have been written by him, and which ones were certainly not written by him. The four letters which most scholars agree were not written by Paul are Ephesians, 1 & 2 Timothy, and Titus, and our passage this morning was from 2 Timothy. 1 & 2 Timothy then, appear to be letters written by a second or third generation follower of Paul. We know there must be some distance between Paul and this author, because when you compare Paul’s authentic letters with 1 & 2 Timothy, you find a lot of differences. There are theological differences, there are stylistic differences, and there’s a different set of vocabulary being used, such as the word ‘myth’, which you find in Paul’s disputed works, 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus, but in none of his authentically attributed works. So, these letters are falsely attributed to Paul. But is that a big deal?

Well, again that is debatable. In the 21st Century, we take a very dim view of falsely attributing authorship, a cultural attitude driven by copyright policy, but it was surely not always this way. Before the printing press we almost certainly had a more fluid sense when it came to attributing authorship. If you take England for example, printing presses came into prominence in the 16th Century, and the 17th Century is when parliament passed its first piece of legislation protecting copyright. And this happened for the very simple reason that a stationary company would print something, and then someone else with a printing press would take that pamphlet or book, and produce a cheaper knock-off version. ‘The Licensing of the Press Act 1662’ made it illegal to print another stationary company’s material for a two-year period. Today, copyrighted material is protected for the life of the author plus 70 years, and that number is likely to rise. So, copyright law has certainly affected cultural attitude concerning authorship. In pre printing press cultures, with this more fluid sensibility at play, one can imagine, for example, writing a piece in which you invoke the spirit of a particular person, say Paul, to further their cause, or champion their ideas - not as a contemptible act, but in homage to what they represented. Homer, the author of The Iliad and The Odyssey is another good example of this. In Homer’s case though, he may not have been a historical person at all, more like a shared tradition, or a shared pen name, which various Greek authors used to produce that corpus of work.

That is to frame Paul’s disputed works then in the most favourable of terms, but perhaps that is too generous. After all, in the 2nd and 3rd Centuries there is a lot of material being produced which is being falsely attributed to biblical figures, such as a lot of the Gnostic material for instance, like the Gospel of Thomas, or Gospel of Judas, or the other Gospel from which we heard – the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, in which her secret teachings are recorded. All of which are (as far as we know) falsely attributed works. So perhaps, Paul’s disputed letters are more like that, texts that should have never made it into the Bible, but were believable enough, and theologically in-tune enough, that they slipped in under the radar, and began to be circulated in the early church, thus establishing them and earning them a place within the emergent canon. Whereas gnostic texts, such as the Mary Magdalene’s Gospel, are so far removed from what we find in the New Testament otherwise, that it’s not at all surprising that that book, along with other such Gnostic texts, were never for a moment considered to be a part of the emergent canon, which by the mid 4th Century was pretty well established.

Athanasius, the Bishop of Alexandria, published a list in 367 CE of the books he considered legit. The 27 books on that list are the same 27 you’ll find in the New Testament today. As an aside, Gnostic texts generally have this shared theme of secrecy, secret words from Jesus conveyed to us via Mary or Judas, or someone else within his close circle. And as secret words, conveyed to a select few, it is impossible for such books to carry that universalising spirit that the books of the New Testament share. But despite Paul’s disputed letters making it in, and such Gnostic texts not making it in, these falsely attributed works (whether in the Bible or not) have a common feature. And that is that they all insist upon their own authenticity, often going way over the top in the process, almost as if they’re anticipating us questioning their authenticity. The lady doth protest too much, methinks. So, as we heard in the Mary Magdalene Gospel, we have the apostle Andrew doubting Mary’s claims (in other words setting Mary up to defend her claims), and then Peter himself coming to Mary’s defence - in other words a contrived narrative which allows the text to labour the point that this is all real – no really it is! And you get the same thing in 2 Timothy, but in 2 Timothy, it’s done by referencing these absurd myths that those who have turned away from the truth have embraced. Those clamouring after teachings which satisfy their desires, their will.

Could this possibly have been written with a straight face? This is someone writing about the ills of embracing false narratives, while pretending to be someone he’s not. Literally a myth decrying myths. But nevertheless, as I said, it made it onto that list created by Athanasius - 1 & 2 Timothy, two of the 27 books deemed acceptable. I feel it’s essentially a survival of the fittest mechanic at play. The theology of 2 Timothy differs, but it doesn’t differ Mary Magdalene style, it's not off into the deep end, it doesn’t reference any secret gnostic Jesus teachings. It doesn’t reference any ethereal plains, or closing epochs. And as such, it makes onto the canonical list.

Knowing all this, I’m left not really knowing what to do with 1 & 2 Timothy. I’m tempted to rank everything in the New Testament, in terms of its authenticity, and in terms of its proximity to the historical Jesus, with the Gospel of Mark at the top, and then in descending order, going all the way down, through all 27 books, until somewhere at the bottom I find 1 & 2 Timothy. The difficulty, however, with this approach, in framing the problem in this way, is it still defaults to this idea that there is an uncorrupted capital-T truth there at the centre of Christianity - there in Jesus, there in so-called “original Christianity” - and if only I can wade through all the deception, all the power play, all the opportunism that has shaped and corrupted the texts, there at the centre I would find the pearl of great price. And I cannot articulate enough how conflicted on that question I feel.

Intellectual, academically, it seems totally false, totally absurd. It seems to me that the whole thing must have been cultural Darwinian forces at play, all the way down, but nevertheless, I cannot let go of my non-rational perception of things, my intuited perception of things. My sense that somehow, there at the centre of Christianity, not so much in the text, but in the core of my being, there is a greater reality. Here in the Kingdom of God, here in Christ-consciousness there is a truth, that does, somehow, cause me to soar upwards and above, to transcend the absurdity of this game that most people (most of the time) are playing. Because I can’t stand it. It’s a sick joke to me. It’s a chess game that everyone is seemingly wed to, and when pieces are played against me, what am I to do? Am I to respond, do I parry their moves, do I play their game, or do I simply laugh? Do I simply draw in the sand with my stick? What unfolds is bewildering, but when considering the Bible and its authorial complexity, let us try not to throw the baby out with the bath water.

Amen.