Part 1

This morning’s service is on a book. It’s obviously difficult to say what is the greatest book ever. Okay it’s not difficult, it’s impossible. What does such a question even mean? Best in whose opinion? My best, your best, their best? There is no objectively universal standard for ‘book goodness’. I am reluctant however to say that ‘book goodness’ is therefore entirely personal, entirely subjective, entirely down to your own opinion. This may make me an elitist of sorts, but I am going to trust the book critics’ opinion more than I trust Joe Bloggs down the street. I often think this when it comes to film. You know that really irritating person who won’t watch a film until he’s read the review – well I’m afraid to say that’s me. It doesn’t matter to me how ‘cool’ my brother says the film is, if film critics say it’s terrible (which if my brother says its good is quite likely), it’s going to take a lot to persuade me of its merit. When I was younger, my dad had a narrow hardback book on his shelf, called ‘The Great Books of the Western World’. The idea of reading all the great classic works of literature always had a somewhat romantic feel to it. Today of course, no one would buy such a book; they would go online and google ‘the greatest books ever written’. If you do so, you will find many many lists of the top ten books, the top hundred books, and so on… Books that you normally see at the top of these lists include: the Bible, Homer’s ‘The Iliad’ or the ‘The Odyssey’, James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’, Moby Dick, War and Peace, The Great Gatsby, The Divine Comedy, and so on. But there is a great deal of disagreement. Once upon a time when a book sat upon your shelf telling you what the best books were, it felt more definitive, you knew if you were reading one of the best books. Today we do not have that luxury, we are saturated with all the lists and opinions we could ever possibly want. The luxury of certainty is gone. I did, however, find one website that brought a little bit of objective rigor to the question. Instead of just asking a critic, or literary magazine, what its opinion was of the top books ever written, it took all the lists online and compiled them into one single list, essentially using the superior, alternative vote system, to give us a definite answer. Well, an answer. I’m not sure it really has much more merit than any other list, but let’s just pretend it does. So, the book at the top of this superior list was, ‘In Search of Lost Time’ by Marcel Proust. Now I had not read this book, but it seemed like it was something I should read. I looked it up, and learnt that it was a long book, a very insanely long book. In fact according to the ‘Guinness Book of World Records’ it is the longest book ever written. It’s over twice as long as ‘War and Peace’. But, still, if it’s supposedly the greatest book ever written, maybe I should read it anyway… So I kind of cheated. I searched around for an abridged version of the book, which was much more manageable, but as far as I’m concerned that counts. So, I can now claim, just about, to have read Marcel Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’.

Marcel Proust (1871 - 1922)

Marcel Proust lived around the turn of the 19th Century. He was, as his name suggests, a Parisian French man; his book ‘In Search of Lost Time’ is a first-person fictionalized biography about him and his search for purpose and meaning in life, to stop wasting time, and to start appreciating the present moments of his life. The book has a reputation, partly due to its length, partly due to the book’s supposedly obscure nature, and partly due to it being French, for being a book read and spoken about by elitists: to have read ‘Proust’ is to have acquired a social and spiritual badge of distinction. Monty Python satirized this reputation in a sketch they did, ‘summarizing Proust’, in which the contestants were to summarize Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’ in 15 seconds, first in evening dress, then in swimwear. Of course, it’s funny because it’s impossible, one cannot summarise a book with over a million words in under 15 seconds. They failed to do so, as I will fail this morning, but hopefully I should get a bit further along than the Pythons. So, to begin with this morning, a notable extract…

“I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate than a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory—this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was myself. I had ceased now to feel mediocre, accidental, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I was conscious that it was connected with the taste of tea and cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savours, could not, indeed, be of the same nature as theirs. Whence did it come? What did it signify? How could I seize upon and define it?”

Part 2

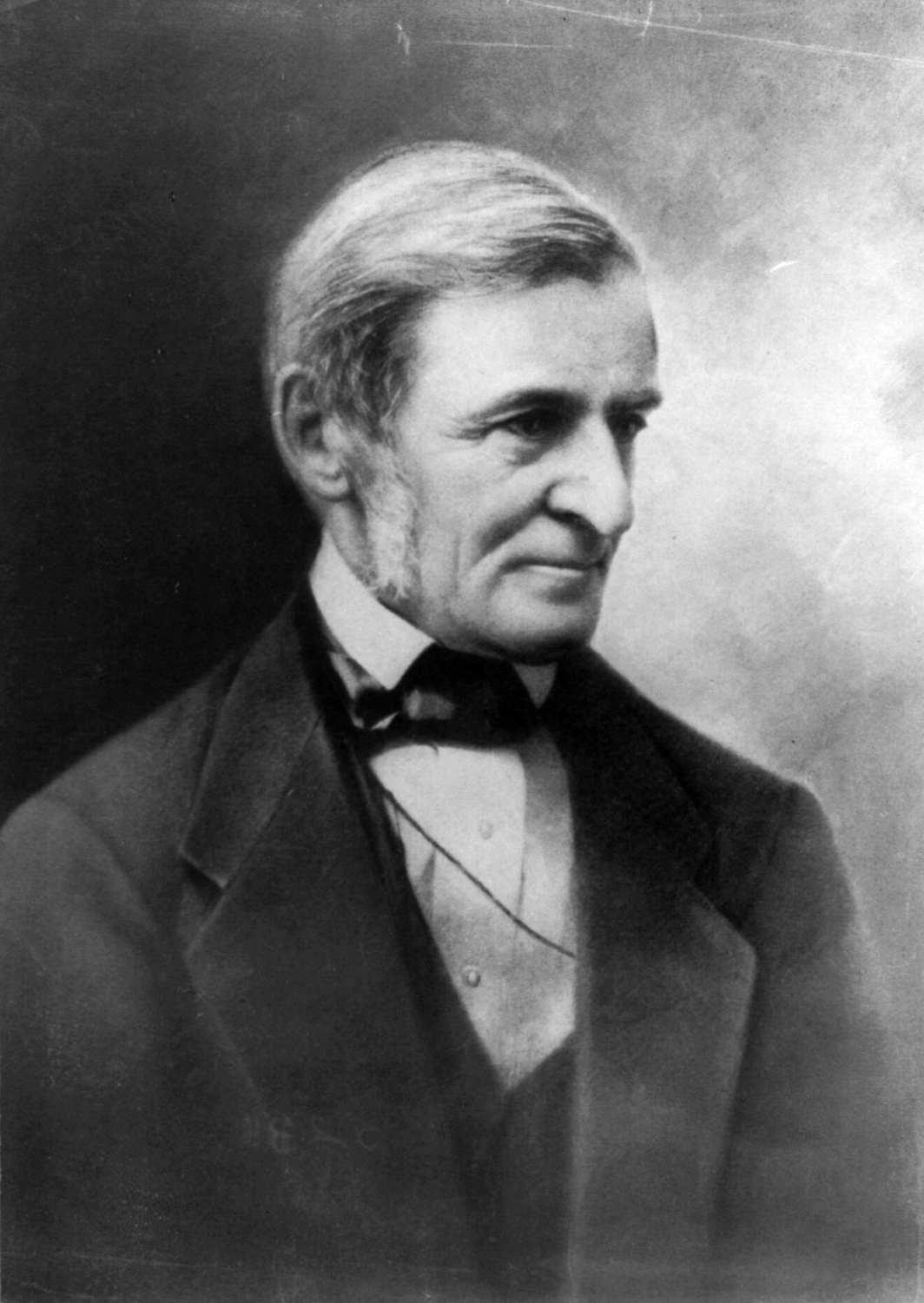

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 - 1882)

Many writers shaped and informed Marcel Proust: Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, John Ruskin, Edgar Allan Poe. But one influence for me stands out. It was detectable in the reading we just had: a spiritual experience had through nature, the uncovering of truths which go beyond what our senses can tell us, goes beyond even what our intellectual faculties can grasp, towards the inexpressibly transcendent. I am talking about the 19th Century American ‘Transcendentalist’ movement (I am talking about Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau), which, as you all may know, is a philosophical movement within Unitarianism which in some ways endures within our movement, continuing to breathe into us new life. Marcel Proust was very much a disciple of Emerson. There are nods throughout ‘In Search of Lost Time’ to Emerson regarding his thoughts on nature, the ‘transcendent’, and Emerson’s brand of thoughtful individualism. Indeed, the Emerson quote, ‘Life consists in what a man is thinking of all day’ goes a long way in capturing Marcel Proust the man, and the value he placed upon the journey of burrowing into one’s inner-self, towards ultimate purpose and meaning. Being an Emersonian of course made him very much a fan of Thoreau’s ‘Walden: Life in the Woods’. Remarking upon Walden, Proust said “It is as though one were reading them inside oneself, so much do they rise from the depths of our intimate experience”. Proust even came close at one stage to being the first to translate ‘Walden’ into French. As an aside, it is interesting to note the similarities between Proust and Thoreau, as on the surface they could not have been more different: the genteel Parisian and the American manly woodsman.

Proust's Tea & Madeleines

So, to summarize Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’: he is in search of life’s meaning. He attempts to find it in several different ways: first, by climbing the social ladder, and associating himself with the virtuous and noble aristocratic class, but once he achieves this, he learns that in fact they are no more virtuous and noble than anyone else. What on the surface appears regal, and dignified, up close can be far from it. And so he broadens his horizons, broadening the spectrum of people he desires to have in his company, in the process letting go of the widely-held myth that ‘out there somewhere’ there is a superior group of people, which would enrich and make our lives more meaningful if only we could discover them, if only we could find them, and associate ourselves. And so, he turns his attention to ‘Love’, the love of a beautiful girl. The depth and significance of joining our heart, and our souls, and our bodies entirely to another, in a special and sacred bond, to know and to be known. But again, Proust finds this ideal in reality lacking. It is impossible to be truly known, and to truly know. We cannot really be understood – the very depths of our loneliness cannot really be overcome. And so, finally, Proust turns to the last possibility for finding meaning and purpose: art. Art in the broadest possible sense. Through art, we are given a fresh set of eyes to see the world. “This is the real voyage of discovery, it consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” In this way, the everyday and mundane can be enlivened, if we look upon it with fresh eyes, like a child does. This is achieved through a creative sensibility, a desire to uncover freshness, a desire to look at the familiar in new ways. The hawthorn hedge is not just observed as a hawthorn hedge, it is considered in a multitude of ways: the chapels and towers, the shapes resemble its beauty and majesty, which invoke within us the feeling of being in sacred space, as if before the very altar of God. The way the light comes through the leaves, resembling windows on the ground, through which the world shows up differently. The fact that in this moment, this hawthorn hedge shows up in a way as it will never again; season’s change will bring with it new and different beauty. The hawthorn hedge to Proust also awakens dormant memories, like the tea and cake did. In the hawthorn, memories of childish times come to mind, times of joy and free abandon. It is as if, in this multiplicity of meaning, sight and sound, there is an orchestra at play just for us. It is the promise that there is yet a depth to be uncovered within each moment we inhabit, a reminder to lean into life, and not be drawn into the habitual lifeless mire.

The Flowering Hawthorn Hedge.

And this in turn says something about our go-to explanations about life and our world. We so naturally, slowly gravitate towards comfortable narratives through which we frame everything, ignoring to our peril the true breadth and complexity, and thus beauty, of all this. The habitual, and the proper, can so easily dull potentiality. I began this morning by falling into that very trap. What is the definitive list of the greatest books ever written? Finding the correct, definitive standard, by which we can measure the worth of our actions, is such a tempting prospect. Reading ‘In Search of Lost Time’ is made to feel subjectively all the more valuable, in the knowledge that it is the greatest book ever written. It can seem easier to read, and maybe even more pleasurable, if we allow ourselves to be momentarily deluded. But of course, we allow ourselves to buy into delusion of this kind all the time. Our internal world is shaped through our appeal to certain kinds of authority, or normative worldviews, or ideas we’ve always had. This in turn shapes our beliefs, and even shapes what we value, or what brings us joy. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with that, but it could dull us, it could dull us to the world which shows up, tempting us to forgive the unforgivable, or not seek justice for the victim, or to allow the hungry to just go on being hungry. Through the artist, we are given new eyes, new freshness; and yes that will destabilise us, it will make us less sure, it forces us to question afresh ourselves and the world around us. And that is the brilliance of Marcel Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’, not only as a parable imploring us to seek out new eyes, but also as a piece of art in itself, which shows us the multiple beauties in the tea and cake, and in the hawthorn hedge.

Amen.