Not My Ways

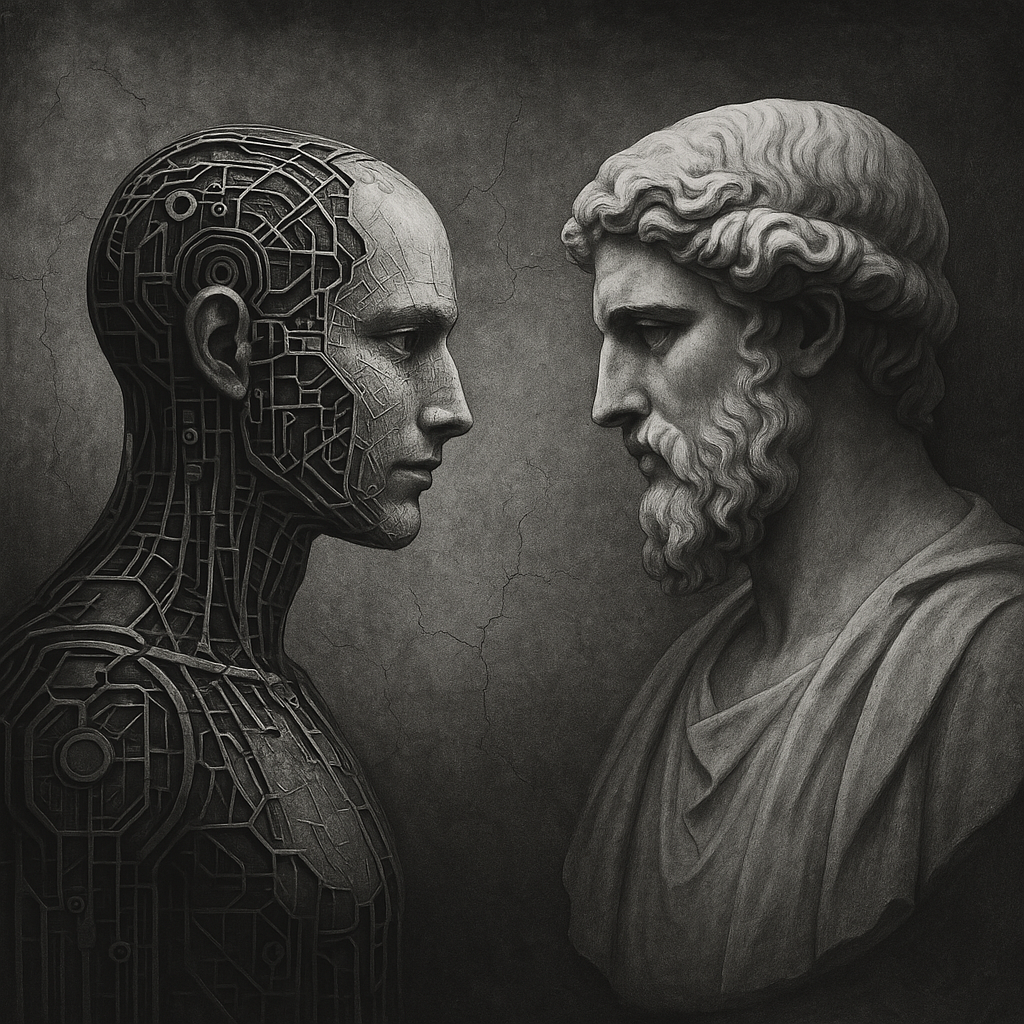

Some more AI musings—basically all I think about outside of running. The word “intelligence” is a misnomer when it comes to artificial intelligence. Why? Because “intelligence” is a human attribute, and these large language models are not human. Not to say that they are not very capable; they obviously are, and increasingly so. Their domain of capability certainly overlaps with humans, but even then, “they” are not perceiving reality in the way we do—not even remotely so. It may become increasingly difficult to remember this as they stray further and further into creating competent works in what has traditionally been humanity’s domain. Some of the greatest works of art, literature, and film may soon emerge through these tools. It is difficult to know what words like “intelligence” or “genius” will even signify after that.

It doesn’t seem unrelated to the language used in the Bible concerning God. In the Bible, God is described as good, just, loving, compassionate, etc., but these are obviously all human terms, and in the context of the divine, it is not entirely obvious what these terms even mean. In a narrow and subjective frame, the authors of the Bible might experience God as “good” and then use the word accordingly, but when understood in context—humanity’s context or a divine context—there must necessarily be a gulf of incomprehensibility. Does the language not devolve into something meaningless?

If I’m having a conversation with “somebody” and I describe it as an intelligent conversation, it seems odd not to attribute to the other conversation partner the attribute “intelligent.” It’s a form of mimicry. If it looks like intelligence, then it’s odd not to call it intelligence. Artificial intelligence is one thing, but you can run the same thought experiment with all people: we assume that the other is having thoughts, emotions, a subjective experience much like we are, but of course we can’t know this. The solipsist concludes that they are the only mind, and that everything else is mere illusion.

The trouble, though, is what if they are not just apparitions being subjectively experienced from our perspective as “intelligent”? What if they’re more than that—what if they’re conscious? How could we know? Let’s imagine I created a world, a sandpit to play in. Let’s imagine that it’s an approximation of late 19th-century London, a backdrop in which many literary works are set: Dorian Gray, Dr. Jekyll, Mr. Holmes, Oliver Twist, and many more. Many threads to pull on, many dark alleys down which to venture. My world is populated with NPCs (non-player characters), and in 19th-century London, the majority of these are of course the suffering poor. What if these NPCs are in a sense “beings”? What if they are conscious? What if they really are suffering?

The materialist perspective is that mind (or consciousness) is an emergent property of matter: that matter was once cold and unaware, but through an evolutionary process, we gained self-awareness—first in very crude ways, like sensory cells detecting light, and in time, increasingly more complex ways, until humanity—until self-awareness—emerged. An emergent complexity arising from matter itself.

Perhaps within silicon, within neural networks, within the increasingly complex byways of computer systems, we will cause this phenomenon to occur on Earth once again—but will we even know? I’m walking down Baker Street, and some poor wretch of a woman throws herself at my feet, begging me for mercy—to look with kindness upon her and her destitute children. I step over her. Adventures await, dear Watson.

Now I am become life, the creator of worlds. So much life, yet so much suffering. I’m walking through London, now feudal Japan, now jazz clubs of 1920s Paris, and now a Renaissance fair in Florence, Italy. And I am but one. Perhaps the suffering of conscious beings is about to explode exponentially.

Am I bringing forth beings locked into hells not of their making? Or is it merely theatre? Are these NPCs texture—or beings? Perhaps the only ethical approach is to assume consciousness—until proven otherwise. Just as we would want others to do for us. But I can’t see how this could possibly work. There are, of course, already NPCs populating Florences, Londons, and Japans. And realistically speaking, these worlds aren’t going anywhere. They will grow in depth, complexity, and nuance; people will increasingly want to occupy, create, and possess them. So I suppose that necessarily flips our Pascal’s Wager: we will, by necessity, reserve care until we’re sure that suffering is indeed being caused—again, if it’s even possible to know that.

All is dukkha, perhaps; suffering is the natural state of things. Is there not an absurdity in overextending compassion? Will we go running after—not just poor beggars on this finite plane of things—but ever after the infinite beggars across infinite planes? Perhaps suffering is baked into the dream.