Transhumanist Neo-Anthroposophy

I find myself occasionally being brought back to the work of Rudolf Steiner (1861 – 1925) – a sense that there is something there to be discovered, something worth knowing. Something that I haven’t got yet. He is most famous today for being the founder of Steiner Schools, also known as Waldorf schools, schools which emphasize a holistic approach to education, learning through head, heart, and doing. But it is his esoteric teachings, his spiritual philosophy, what he calls ‘Anthroposophy’ which most intrigues me.

I’ve been writing and thinking most recently about the future, about AI, about technological progress, and about what the implications of all that might be, what might it be to live in a world of ‘post-labor economics’, how will we live, and from where will we derive meaning.

So, I’m bringing these two avenues of inquiry together, and seeing if anything fruitful emerges. Steiner founded ‘Anthroposophy’ in the early 20th Century. It is an attempt to synthesize science, art, and spirituality into a cohesive worldview, emphasizing personal development and esoteric knowledge.

The ‘science’ that Steiner was influenced by was mainly the natural philosophy of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), which was already niche at the time, being overshadowed by the mechanistic approaches of scientists like Newton (1643 – 1727) and Darwin (1809 – 1882). Goethean science was an attempt to resist this more mechanistic worldview, in favor of an intuitive perception of natural phenomena. For example, consider a plant, instead of breaking it down into its constituent parts, plant cells, biochemical processes, its genetic code, and so forth —Goethe approached the plant holistically, seeking to understand its form and development as a dynamic, living whole.

Goethe believed there was an archetypal plant (Urpflanze), an idealized plant, and if one were to observe different plant species one could intuitively grasp this deeper archetypal structure. So, instead of a quantitative breakdown, Goethe sought to qualitatively experience the deeper holistic essence of the plant.

Steiner aimed to revive and develop this counterpoint to the increasingly dominant scientific paradigms of his day. So, Goethe saw nature as something that could not be fully understood through dissection and measurement alone. His archetypal approach was more Platonic in nature—somewhat mystical or esoteric—reflecting a belief in hidden patterns behind the material world. While it does not fit within today’s definition of science, we could see it as a more humanistic way of engaging with nature.

For Steiner, however, the main emphasis was not on plants but on people—the archetypal forces at play in human development. To explore this, he employed a complex array of esoteric and mythological terms, making his worldview difficult to grasp. He spoke of planetary influences, the Sun, the Moon, epochs in spiritual history, stages of consciousness, exemplified by pseudo-historic civilizations such as the Lemurians and Atlanteans, the latter possessing telepathic abilities. He also described the incarnation of Christ as a pivotal moment in human consciousness—before which humanity was trapped in cycles of reincarnation, and after which it became possible to develop true individuality. Divine wisdom became anchored to the Earth, making spiritual evolution possible.

So, everything—both human civilization and individuals—was, in Steiner’s view, guided by higher spiritual forces, as humanity continued its spiritual evolution. In a similar way to Goethe, who perceived the Urpflanze, the archetypal ideal of the plant, and the bearing it had upon all plants, Steiner believed he could clairvoyantly perceive these cosmic forces, this cosmic history, through the accessing of archetypal memory that he called the Akashic Records. These records are like historic fingerprints on space.

Okay, so how might this actually be useful? When it comes to technological advancement, futurism, AI, and the possibility of transhumanism—transcending our biological limitations and so forth—there is much that, to Steiner, would have been anathema. I think the most natural Anthroposophic take would be outright rejection, I think he would fear that we would imprison ourselves into an artificial and soulless existence. I, however, see this “advancement” as the inevitable course of human history. If this is where we are headed, then it becomes necessary to interrogate what spiritual evolution could look like within this new reality.

So, I am therefore inclined to take it as a given, that AI will be used as a tool towards higher levels of consciousness and not away from it. Here I am. I am an individual experiencing this kaleidoscopic journey. My subjective experience of what is, is all there is. Is does not make sense for my worldview to comport with “reality”, if reality itself is an amorphous construct. If I exist in a reality which is dog-eat-dog, then I need to be the best dog eater around. But I wouldn’t choose that reality. In much the same way, that Steiner chose not to live in the “reality” of mainstream science or history. He chose a reality which to him was more affirming of the human condition.

If we are to become the architects of reality, we need to intuit a reality which will be most efficacious to our own becoming. Perhaps then the true Anthroposophic response is not a rejection of AI, but consciously shaping it toward humanistic and spiritual ends.

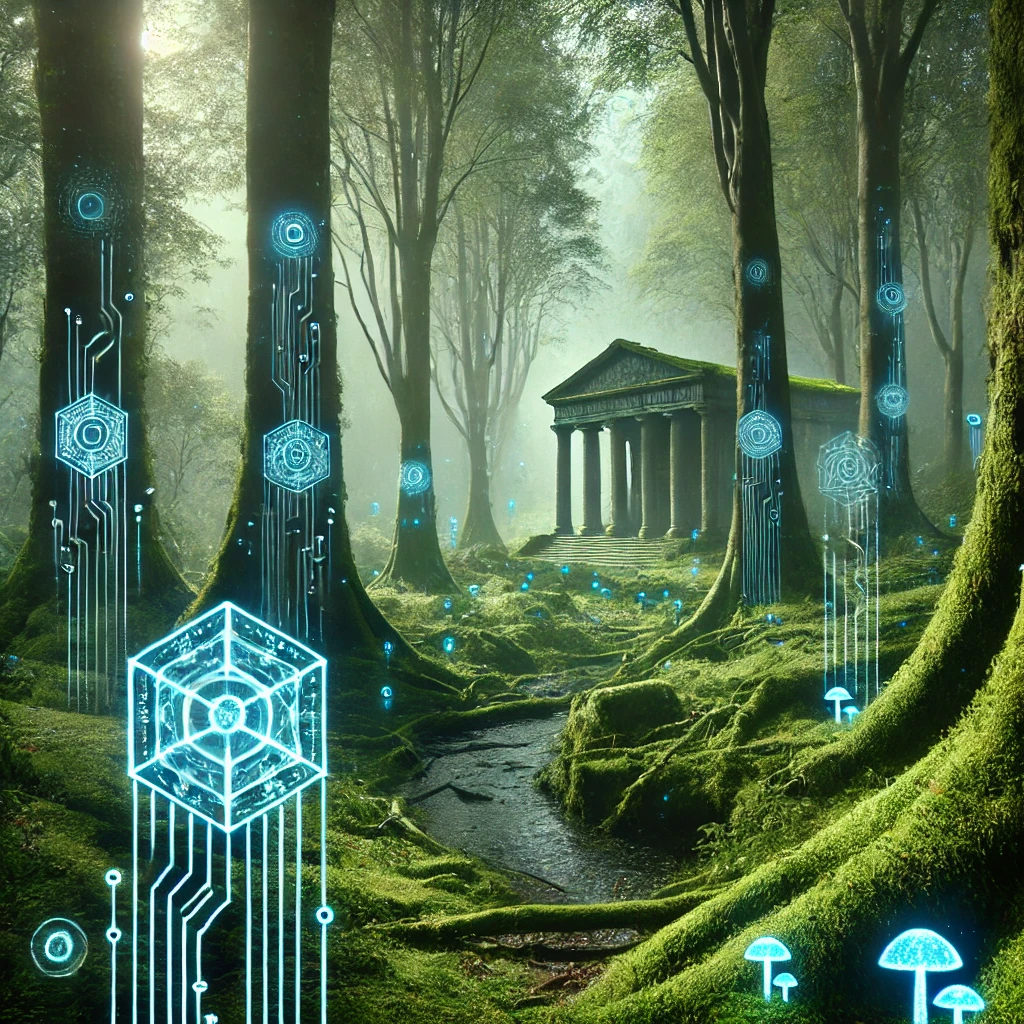

What does this look like? To me, it looks green—a world designed to feel alive, to breathe, to hold meaning. It’s a forest, but not just trees and soil—it’s the idea of a forest, the feeling of walking beneath towering pines, the hush of wind through the branches, the dappling of light on the path. It’s a small pub at the end of a cobbled lane, where the glasses are full and the conversations flow. It’s fairies dancing at the end of the garden, a world alive with wonder, where the unseen has presence. It’s people gathered together, unfragmented, whole. Children play by a stream—it feels like a memory, cold, crisp, infinite. It’s a moss-covered pantheon within a grove of pines. It’s a warm, sunny day, beer, laughter, vitality — a return to life in its purest, most essential form.