The Unseen Watcher

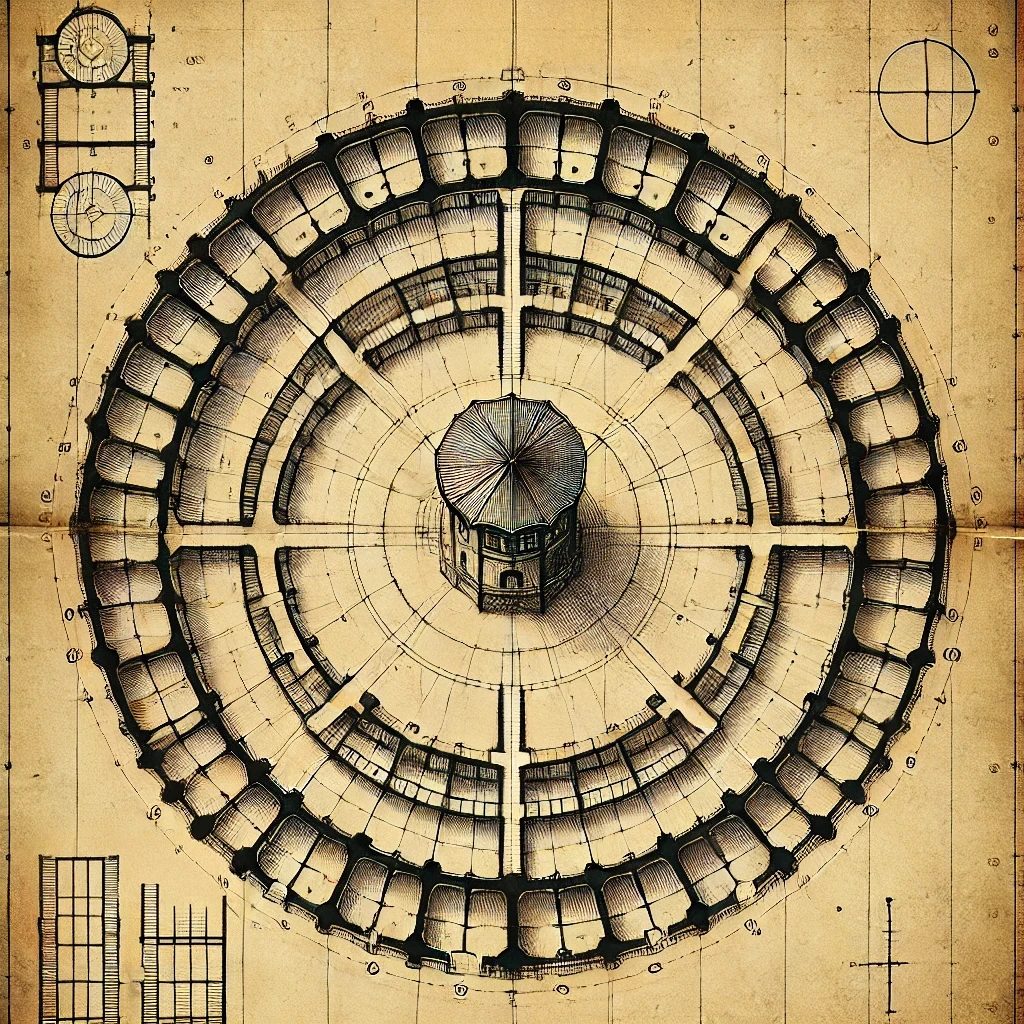

I have been reading about prison design, specifically Panopticon prisons. A Panopticon prison is a circular prison design where a central watchtower allows guards to observe all inmates without the prisoners knowing whether they are being watched, creating a sense of constant surveillance and self-regulation. This design was originally conceived of by the father of utilitarianism, Jeremy Bentham – it is an outworking of his utilitarian philosophy – which seeks to maximize happiness for the greatest number of people. He made his design in 1785.

In 18th-century Britain, corporal punishment was a common form of discipline. One might be flogged, sentenced to hard labor, or sent to a penal colony such as America or Australia. Oscar Wilde comes to mind as a notable individual who was sentenced to hard labor for gross indecency as late as 1895. His punishment consisted of being chained to a penal treadmill – a large wooden structure which resembled a water wheel. Individuals would be forced to climb it for up to six or more hours a day. Wilde never recovered from his grueling two-year sentence; the physical and mental torment led to an early grave at the age of forty-six. Soon after his release, Parliament passed the Prison Act of 1898, which officially abolished the treadmill and all other forms of cruel hard labor.

It was suffering of this nature that Bentham’s Panopticon design sought to eradicate. For Bentham, the goal was to maximize overall happiness while utilizing the fewest resources possible to achieve that end. Bentham extrapolated his philosophy into architectural design – prisons, factories, hospitals, asylums, and schools. The control mechanism would be the ‘unseen watcher’; the perception that one is being constantly observed causes the individual—be that the inmate, the worker, or the student—to self-regulate their behavior, ultimately leading, in Bentham’s reckoning, to a more orderly and rational society. In theory, the Panopticon is more efficient and cost-effective too, as it reduces the number of guards required to maintain order. Governmental welfare economics today is influenced by Bentham’s philosophy – that we ought to allocate public funds in such a way that it generates the most benefit at the lowest cost.

Beginning in the early 19th century, many prisons began to integrate aspects of Bentham’s design into theirs. However, due to cost constraints, the Bentham Panopticon ideal was never fully realized. That is, until Gerardo Machado, the president of Cuba, had his ‘model prison’ built in 1926 – the Presidio Modelo on the Isla de la Juventud. Over time, the prison became notorious for being overcrowded and having inhumane conditions. There were riots and hunger strikes, which ultimately led to it being closed in 1967. I had a look on Google Maps to see if the structure was still there. I found that the ruins of these five round buildings remained in place. Seeing them there, I can’t help but sense their eerie, menacing, and dystopian presence.

On 26 July 1953, Fidel Castro led a small group of revolutionaries in a failed attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. Many of the revolutionaries died or were imprisoned. Thirty of the surviving rebels, including Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl Castro, were imprisoned in the very same Presidio Modelo. In a letter concerning the prison, Castro wrote, “What a fantastic school this prison is… From here I’m able to finish forging my vision of the world…” After 22 months in prison, political pressure secured their release. Castro fled to Mexico, regrouped, and in 1959 returned to overthrow the Cuban president, appointing himself prime minister.

Obvious parallels have been made between Bentham’s Panopticon and the surveillance state, workplace monitoring, and digital privacy. As more of our lives play out online—shopping, socializing, playing, working, etc.—there is the obvious fact that we have all accepted into our homes the unseen watcher.

Michel Foucault, the French philosopher, wrote the book ‘Discipline and Punish’ (1975), in which he critiques modern power structures. He uses Bentham’s Panopticon as a metaphor. Whereas society used to maintain order through physical torture and public spectacle, there is now a more insidious system of surveillance, which shapes individuals’ behavior through constant observation and self-regulation—a shift from targeting the body to controlling the mind. Control of all individuals has mechanized into the system itself; we all internalize norms, making control subtle yet more effective than overt force. In this way, the kind of surveillance one sees at play within a Panopticon prison is a system of correction which, in reality, extends into society at large.

I would say I have a natural libertarian streak, maybe even a touch of Oppositional Defiant Disorder, with a strong preference for maintaining my autonomy, liberty, and freedom. It feels like Foucault here is identifying something true. He would not, however, jump as a corrective to the kneejerk utopian alternative, and rightly so. One cannot imagine a world with no surveillance or coercion at all. Culture is always going to coerce our preferences, and Betty next door is always going to watch us disapprovingly through a crack in the blinds. There is obviously a tension here. There is not an obvious ideal to shoot for. My imagination has me forsaking the Kantian imperative in favor of selective rules for thee, but not for me.

I guess the real concern is excesses. It brings to mind the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which involved the unauthorized harvesting of personal data from millions of Facebook users to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the Brexit referendum. This data was used to create psychographic profiles for individuals and then to serve them highly personalized political ads to sway their opinions. It remains unclear how effective, ultimately, these efforts were, but the implementation sets a worrying precedent and obviously raises major ethical concerns. This goes beyond Foucault’s thesis. Cambridge Analytica didn’t just observe; they actively used data-driven content to manipulate populations on a grand scale.

Or one could consider the YouTube algorithm. I think it feels more benign because, unlike Cambridge Analytica—where manipulation is orchestrated from above with a specific directive—YouTube’s influence is more passive. If, for instance, you watch some extremist material on YouTube and, as a consequence, are recommended more extremist material, it’s kind of your own fault. The only sinister ulterior motive when it comes to YouTube is getting you to spend more time watching YouTube. And if you just so happen to gravitate towards content on global Jewish conspiracies, well, the algorithm doesn’t care. The alternative almost feels more problematic. I don’t want an algorithm that gently steers me back towards whatever content “it” deems safe.

All that being said, I think there is a major concern around the encroaching manipulative power of the Unseen Watcher. If you’ve read my stuff before, you will probably know that I am very much a techno-optimist. I think there is a strong likelihood of huge upside in the not-too-distant future. And I’m not going to be jumping on the we’re on the techno-fascist hype-train anytime soon. But we’re going to need far more critical awareness going forward; fanboying over any individual is not going to serve us well.

With the power of AI, one can imagine Cambridge Analytica-type dystopian scenarios on steroids—not the crude hammer of a political ad appearing on your social media app, but a sophisticated conversation partner, gently and skillfully maneuvering you towards a perception of reality that serves some elite interest. Will artificial intelligence coerce my perception of reality? Of course, it will. It almost certainly already has. But I don’t want that power concentrated in anyone’s hands. I want it to be anarchic, decentralized, open source. Okay, I’ll admit it—I do want the utopia.

Look at that, I managed to write this whole article without mentioning Orwell.