A Taste of Deeper Things

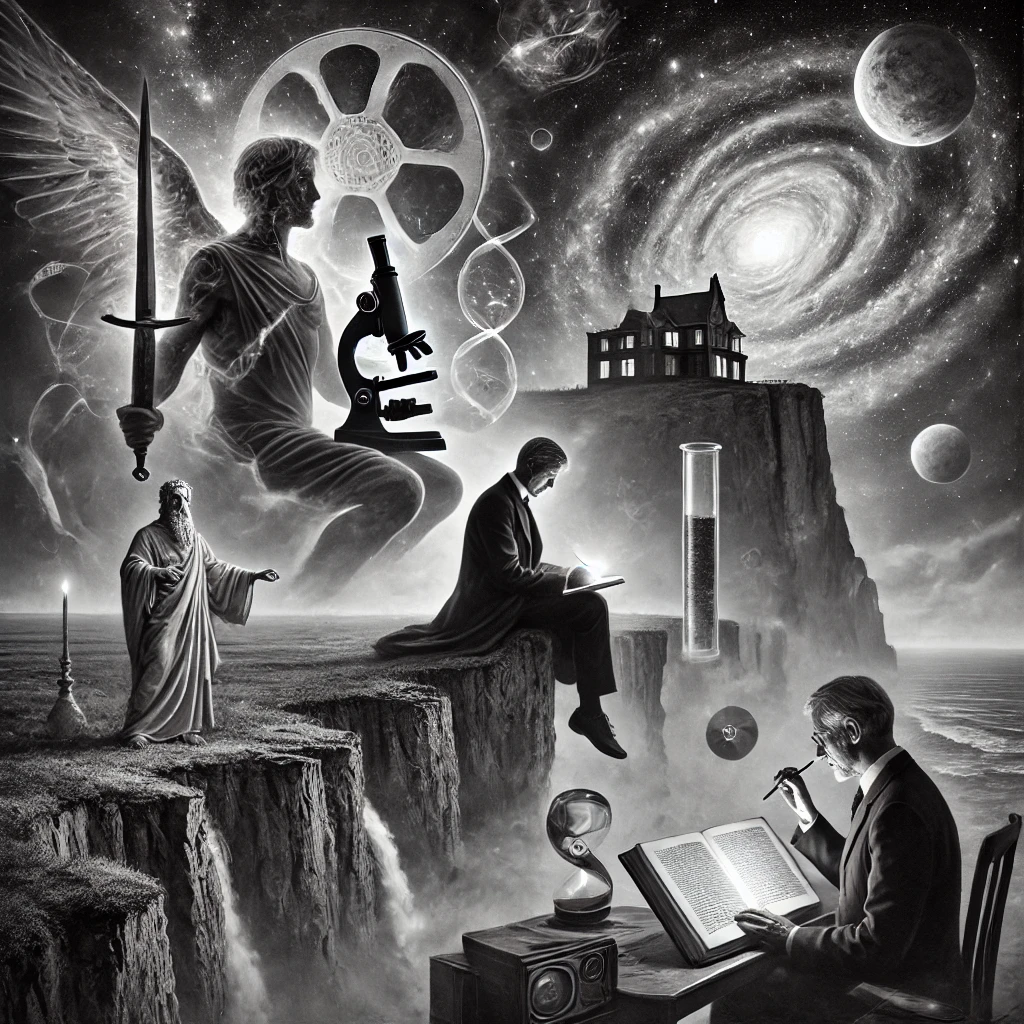

Lately, I can’t seem to stop thinking about taste. Taste is elusive; I know what I like, but articulating why I like it is a far greater challenge. The reasons behind our preferences often defy clarity, as though the very idea of ‘reason’ cannot capture the instinctive pull of our preferences. It remains buried in the unconscious mind—a realm of unspoken memories and intangible connections—where art strikes at chords within the self.

To speak of such things—of taste—is, I think, necessary, personal, and a most human endeavor. For reasons I will explain, I’m going to discuss four pieces of art: a film, a series, a book, and an album, four pieces that I like and that have stayed with me. The four are: Darren Aronofsky’s ‘The Fountain’ (2006), ‘Six Feet Under’ (2001 – 2005), ‘The Rings of Saturn’ (English publication 1998) by W. G. Sebald, and Loudon Wainwright III’s second album titled ‘Album II’ (1971), focusing on the sixth track ‘Saw Your Name in the Paper’. So, on the surface these four pieces are obviously very different. The film is a trippy science fiction romance which jumps around in time. The series is a drama set in a funeral home in Los Angeles. The book is a first-person narrative about a man going for a walk along the Suffolk coastline in England. And the album is a sparse collection of folk songs, just vocals and a guitar.

Now, I will be going into each of these in more detail and attempting to express why I think each of them resonates, but as I have already intimated, I expect I’ll fall short of this. I do believe, however, that something at play has to do with when one is laid out bare, when one strips away pretense, and when one is willing to meet, and be met by, the other. These works extend an invitation to step into their shared emotional space. I’m not that fond of small talk—it can be exhausting and unfulfilling – but in a real conversation there is a sense of mutual presence, where the weight of the moment can be tangibly felt. When one is honest, vulnerable, and real, there is a sense of being on the brink of something essential. These four pieces invite us into this kind of conversation.

In ‘The Fountain’ (2006), starring Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz, the protagonist sets out to discover the tree of life, the tree from the garden of Eden. The narrative draws on the motifs of a knight on a heraldic grail quest. He is on his hero’s journey to discover immortality, healing, and wholeness. Queen Isabella in the 16th Century is on the brink of losing her kingdom to the inquisition; she sends out her conquistador to central America on this most sacred mission. The narrative is non-linear; we jump through three interwoven timelines, each separated by 500 years. The protagonist is now in the 26th Century, having taken on the persona of a cosmic Taoist monk who is operating on a different plain of reality, but no less in pursuit of the tree. “Take a walk with me” a voice interrupts him. He turns his head - he is now in the 21st Century, he’s a scientist. “I have too much work” he protests to his wife in frustration; she vanishes. His wife is dying, she is terminally ill, and he, the scientist, cannot help but labor after a cure. She has resigned herself to her fate, but he cannot stop. The man in all three epochs is the same man, locked into a constant archetypal pursuit after truth, purpose, eternal life, love, everything. It’s an endless cycle, like a Nietzschean loop of eternal recurrence.

The appreciation of something, I think, requires having an eye toward homage. This echoes the sentiment that teaching is the ultimate test of understanding. In the case of art, we’re seeking not just to understand how the note affects us as the recipient, but also the how, the why, and the where. Where is this note positioned within the composition in order to invoke the effect it has upon us?

‘The Fountain’ speaks in a biblical vocabulary, the language of ultimate meaning. This is certainly a large part of why the movie appeals to me: it deals with large, philosophical, existential, psychological, and spiritual questions. These are the waters in which I like to play. When he is in the darkness battling his way through the Mayan savages, he is in the underworld, the shadow world, he is descending in order to uncover the gold, the boon that lies beyond the dragon or the flaming sword, in order that he can carry it back. All very Jungian.

‘Six Feet Under’ (2001 – 2005): apart from the aforementioned essential conversations that it demands, it’s also philosophical and introspective in nature. This is something reflected in all four pieces; there is a tone which speaks to my taste. I’m not making the claim, however (far from it), that these four pieces are all operating on the same frequency. They are not. The high- verses low-brow distinction can be helpful in terms of classification, far less so in terms of determining quality. Elitist art can be crap, and popular art good. I would put ‘Six Feet Under’ in the latter category, good popular art. Among these four pieces, ‘Six Feet Under’ has the highest viewership or listenership.

Death obviously plays a large part. The dead convene with the living, although it’s always the dead as conceived of from the living’s perspective. There is no metaphysical magic here, no voices from beyond the grave. Just the hopes and fantasies of saddened minds confronting the reality of things. The cast inhabits the funeral home, a place where “normal” domestic life butts up against the visceral reality of death. Death, which is painful, at times horrific, at times joyful, and for the affected always creates voids where memories linger. The show induces a dull ache within the sternum. My roommate at university in 2009, the year I discovered and binge-watched all five seasons, reported that I was affected. He said it caused in me a pronounced depression. I think this reflects reality.

It was devastating and brilliant. I have no doubt that it affects my outlook to this day. I think of all the thinkers, from Socrates all the way down throughout history, who have seen confronting the reality of our mortality as the path towards wisdom. And I think that’s what this show is – one long reflection on death. There’s perhaps no moment as poignant as the final scene; I don’t think it’s been bested in TV history. With Sia’s ‘Breathe Me’ playing, Claire Fisher drives across the country; as she does it cuts to each beloved character one by one to watch their death, up until her own, ever begging the question, what makes for a life well lived? Where is meaning to be located?

‘The Rings of Saturn’ is by W. G. Sebald, a German immigrant who lived in England; he taught creative writing in the city of Norwich. His book was written in German and translated into English in 1998. It’s one of my favorite books. He died in a car crash in 2001.

So, on the surface this book appears to be a travel log about a man on a walking tour of Suffolk, mainly along her coastline, and this was not far from where I was living when I discovered and read the book for the first time in 2017. As a result, I visited and walked some of the locations discussed in the book.

The book is about digressions. We’re walking down a trail, we’re reminded of something, and that sends our minds down a rabbit hole of reflections and associations. A little Proustian – a little in memory of things past. In this way, the impressions become the focus, more than the places. He reflects on writers; he recalls a lecturer he knew who had made Charles Ramuz, a 20th Century Swiss writer, his life’s focus; he wrote about European silkworm cultivation; he reflects on the writings of the 17th Century English polymath Sir Thomas Browne, amongst much else. In these recollections and connections, the writer makes it impossible to distinguish fact from fiction. Is the narrator him? Is he talking about a lecturer he really knew, who had really made Ramuz his life’s focus? We don’t know. This uneasiness, this not knowing being invoked in us, is part of the overall effect here.

There is a lot about memory, and a lot about erosion, or atomization, the loss of context and meaning. For instance, he focuses on the buildings that are falling into the ocean along Suffolk’s coastline - there’s a whole world of meaning being literally swept away. Melancholia is both a tone invoked by the writer, and a theme explored. In invoking the works of Browne he says, “all knowledge is enveloped in darkness. What we perceive are no more than isolated lights in the abyss of ignorance, in the shadow-filled edifice of the world” (Sebald, pg. 19).

There’s easily a PhD or two that could be written here, so I’ll jump to the conclusion. The sub-sub-text behind the writing is the Nazis and the Holocaust. Sebald’s father was a WWII German soldier. Sebald was born in May 1944, and the Nazis surrendered a year later. So, Sebald grew up in post-WWII Germany, in a country desperately trying to forget what it had done.

This book then is about the impossibility of discussing such things – if I were take an historical fact - I could say: over six million Jews died in the Holocaust from 1941 to 1945. How can we make sense of such a statement? The point is we can’t. A historical fact as read in a textbook really gets us no closer to the reality of things. It’s all slipping away, it’s all a ghostly apparition. There was much pain – but nothing can be said of that now.

It was on an unusually grey and overcast day in July of last year when I was travelling into Charlotte, North Carolina, on my way to the Novant Presbyterian Hospital. I was listening to the song by Wainwright III, ‘Saw your name in the paper’. It’s a rather somber reflection on fame and the trajectory that life can take. The singer was only twenty-four at the time of release. He’s singing about a girl he knew, “Maybe you’ll get famous, Maybe you’ll get rich”. It has a kind of detached quality to it, as if the only way we can talk about real things is to talk in this more matter-of-fact fashion, to leave our stronger emotions at the door. But they’re very obviously there, unrequited and brewing.

He’s channeling the sage: “Take all the people give, The people all are dying, And somehow you help them live, The people will destroy you, That love will turn to hate.” He’s talking about inevitabilities, like structures, or archetypal patterns at play within the universe. You will be lifted up, you will be exalted, you will represent something far greater than yourself, and as such, it can be turned. It’s not in your control, it’s all the projections of others, smoke and mirrors. I’ve always felt there was a kind of inevitability to everything, some intricate pattern unfolding exactly as you’d expect, if you could only see the whole thing.

My daughter was born in the second week of July. One of the least straightforward pregnancies you could imagine, but here I am, writing, over a year and a half later, and everything is more than fine. I’m not sure if it’s the tone, the themes, or the artistry of Wainwright that makes it resonate with me so strongly, but it does. It feels like someone pouring a glass of whisky and sitting down with you for a deep conversation.

Okay, so as I started with, the point of this was to try and express something of my taste. What makes these four pieces so impactful and meaningful to me? Hopefully something of that has been articulated. Something about sitting in discomfort, and finding meaning in the midst of it. These pieces are pushing us to grapple with the complexity of things.

I’ve been thinking about taste since I posted my article Sunk Cost, the Meaning Crisis, & Taste two months ago. My conclusion there was that writing about taste is a valuable endeavor before the arrival of AGI. As has become increasingly clear, in the coming years technology is poised to upend every paradigm. On the ARC-AGI tests, o3, OpenAI’s latest model has demonstrated significantly outscoring all other models. These developments suggest that AGI may arrive sooner than anticipated, accelerating the need for preparedness. Reflecting this sentiment, Benjamin Todd (80,000 Hours podcast), did a post-thread on X on 12/22/24. It was on what we should be doing personally to prepare for AGI. Here is my paraphrased version of his list: 1. Seek out people that understand what’s going on; 2. Save money, things could get volatile; 3. Invest in things likely to do well in the runup to AGI; 4. Get citizenship in a country that will have a lot of AI wealth, i.e. the USA; 5. Might want an escape plan in place in case the nukes start dropping; 6. Prioritize things you want to be in place before AGI; 7. Don’t do anything crazy in case AGI ends up still being over a decade away. Reflecting on taste doesn’t make his list, but I think it should.

Taste is something which can never be wrong. I could convene a multidisciplinary panel of experts, or I could simply wait a few years and ask a superintelligent AI, but the response would be the same. There is much in coming years that will be upended, many livelihoods made defunct, but can taste be made wrong? Not really.

I think we’re poised to become curators of taste. It strikes me that the future is not that dissimilar to those psychonauts of decades past – using psychedelics in the pursuit of altered states of consciousness - but these, or we, will be tomorrow’s “cybernauts” traversing phantasmagoric landscapes, traversing worlds of taste.